What is a hero?

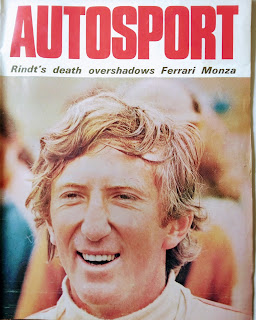

That is a question I have been asking myself in the run up to this date, 5th September 2020 because I know that it is the 50th anniversary of the death of my one childhood hero, the man who is depicted above; Jochen Rindt.

I have been asking myself that because, many years after the all too brief time I had hero worshipping this man (probably no more than 5 months during the summer of 1970), I learned much more about him.

What I learned I admit didn't like. If I had been lucky enough to be a contemporary and been able to meet him, I'm sure I wouldn't have liked him. He was abrasive, short-tempered, arrogant. I am someone who dislikes arrogance, people who are full of themselves, who can be mercurial and awkward. I am attracted to the quiet people, I like the calm and the placid.

Yet he was my hero, at 10 years of age anyway.

Perhaps it would be helpful to look up a dictionary definition: The Cambridge Dictionary defines a hero as 'a person who is admired for having done something very brave or having achieved something great.'

Well, anyone who raced in the 1960s and 70s had to be brave. They were the fighter pilots of their day, driving fragile machines, built of magnesium alloys with fibreglass bodies that burned so fiercely if ignited filled to the brim with volatile fuel with scant thought for protection, on circuits without the modern run-off areas and safety features.

He also achieved great things. The first race I ever watched live on TV was the 1970 Monaco GP. The last few laps were amazing as Rindt flung his Lotus 49C through the streets of the principality in what seemed to be a vain pursuit of Jack Brabham. It was unbelievably exciting and hooked me forever on the sport. That summer of 1970 was a procession of success for Rindt, winning four times in a row in the beautifully modern looking Lotus 72. The deaths of Piers Courage in a fiery accident in Zandvoort and Bruce McLaren in testing at Goodwood were incidental to the 10-year old me.

I didn't know the man, all I could see were his acts. To me he was the perfect hero. His death hit me so hard that I have never had another one, in any walk of life. The loss was just too painful.

What I was left with, because I only ever hero-worshipped Rindt, was how much he deviated in character traits from what I would be drawn to in person. What has also become clear is that this dichotomy exists in other people I have come to admire greatly; Colin Chapman, the Lotus founder and innovator, Werner Voss, the WW1 German Ace, also had similar flaws to Rindt, Voss, for example, had on occasion machine-gunned downed aircrew when they were helpless. It doesn't matter, I revere him as perhaps the greatest ace of the war.

It is interesting, considering I am a novelist, to look at other definitions of hero: 'the main male character in a book or film who is usually good.'

I create heroes - and heroines too. I always have a main character or characters in my books. Yet mine are not 'usually good'. But they are not usually bad either, they are a complex mixture of good and bad, the infuriating and the endearing. In The Last Mountain, the main character is no hero, Mel has been described by many readers as 'obnoxious'! Yet, in the end, most readers were carried along by his battle to survive. More recently in Leviathan and also LMF, the central characters, unnamed in the former Douglas Atkinson-Grieve in the latter, were definitively not boys-own heroes.

I don't consciously seek out the difficult but clearly it fascinates me. It is the flaws in a personality that makes them interesting.

Which brings me back to Jochen Rindt. He was flawed, but by God he was interesting. It's quite clear that he was a really complex character but that is hardly surprising. He was not Austrian by birth, he was German and he lost his parents in an Allied bombing raid when he was two. The next 26 years of his life cannot have been easy, it is hardly surprising he was difficult. Yet he was blossoming, perhaps becoming a bit more at ease with himself at the time he died, at only 28. It would have been interesting to see what kind of person he would have become if he had been able to fully mature.

He never got the chance. Neither did Voss, who was only 20.

I am looking forward to the new book on Rindt that I understand is being published this year. I'd love to know yet more about my one, deeply flawed and yet fascinatingly complex hero.

Rest in peace, Jochen. And thanks for the memories, my hero.

Comments

Post a Comment